TEXT BY ROSANNA MACLAUGHLIN

17.11.2018

One afternoon in the autumn of 2018, when the ground still bore some memory of the recent mon- ths of heat, Catherine Parsonage took me to her studio in Rome. The paintings I saw that day were made during the summer months, which she had spent travelling between the city and the surroun- ding area for work. Each was bound to the group by a shared relationship with time and climate, a di erent entry in an unsettling visual journal.

Catherine and I rst met the previous year, when she was making paintings in a boozy shade of red; paintings of that after-midnight mood, when drink in hand we accelerate towards collision or collap- se, no fucks to give for our morning selves who we leave to pick up the pieces. This new body of work was no less vivid, but the atmosphere had changed. A nauseous kind of vitality had in ltrated her canvases and sketchbooks, and it belonged to a di erent chromatic category: green.

04.01.2019

I have always had my suspicions about the colour green. For instance, I have never felt comfortable watching slow-motion shots in nature documentaries: a single drop of water bouncing o a leaf in a puddle in a rainforest, swamping an insect or small frog and altering its life irrevocably. For similar reasons, time-lapse footage also makes me uneasy: those scenes in which a hairy stem turns from bud to ower to (...)

TEXT BY ROSANNA MACLAUGHLIN

17.11.2018

One afternoon in the autumn of 2018, when the ground still bore some memory of the recent mon- ths of heat, Catherine Parsonage took me to her studio in Rome. The paintings I saw that day were made during the summer months, which she had spent travelling between the city and the surroun- ding area for work. Each was bound to the group by a shared relationship with time and climate, a di erent entry in an unsettling visual journal.

Catherine and I rst met the previous year, when she was making paintings in a boozy shade of red; paintings of that after-midnight mood, when drink in hand we accelerate towards collision or collap- se, no fucks to give for our morning selves who we leave to pick up the pieces. This new body of work was no less vivid, but the atmosphere had changed. A nauseous kind of vitality had in ltrated her canvases and sketchbooks, and it belonged to a di erent chromatic category: green.

04.01.2019

I have always had my suspicions about the colour green. For instance, I have never felt comfortable watching slow-motion shots in nature documentaries: a single drop of water bouncing o a leaf in a puddle in a rainforest, swamping an insect or small frog and altering its life irrevocably. For similar reasons, time-lapse footage also makes me uneasy: those scenes in which a hairy stem turns from bud to ower to dried-out stalk, petals unfurling against their will like sts forced open, life expedited to its ending. In these instances, to see greenly is to see too much.

15.12.2018

The rst painting I turned to in Catherine’s studio was a large canvas covered with a motif of rams’ heads. In the middle of the composition, two of the animals butted up against each other. Like shy, excitable lovers, who bash heads and clink teeth, they didn’t make eye contact despite their proxi- mity. Over the top of the rams Catherine had painted a thick black rectangle, lled with smaller sha- pes and jagged lines. The rectangle had the quality of a drawing made on a phone, as if the skittish movement of her hand had been translated into a perfect, digital rendering of the concept “rough sketch”.

The painting, like all of Catherine’s paintings, registered in my mind as a psychological episode re- layed as a visual allegory. I looked at the silent, bursting scene like a person standing on the other side of a transparent soundproof wall, and tried to receive its meaning. Was the black rectangle a gate shutting the animals in? A layer of dissenting gra iti, middle nger to the pastoral? After a while, it became apparent that it was the oor plan of a bedroom, and that I was looking at a genre painting of domestic life arrived at by unusual means. The rams were bone white, and Catherine had painted the gaps between their heads a thin sky blue. Barely visible in the corners was a faint mist of pallid green.

21.12.2018

On my return to London, green started to feature in my email exchanges with Catherine, who began

to periodically send me quotes she had plucked from books we had both been reading. One gloomy day in mid-November, while sitting at home and watching the rain smudge the London skyline, as if someone had taken their thumb and slowly dragged it across a charcoal drawing, a passage from Olivia Laing’s book The Lonely City arrived in my inbox. Catherine had selected the passage from a chapter on Edward Hopper, in which Laing describes the colour of the electric light that su uses his midnight cafe scenes, in such a way that it becomes a viciously brilliant emissary of modern loneli- ness. “There is no colour in existence that so powerfully communicates urban alienation, the atomi- sation of human beings inside the edi ces they create,” Laing writes, “as this noxious pallid green.”

05.12.2018

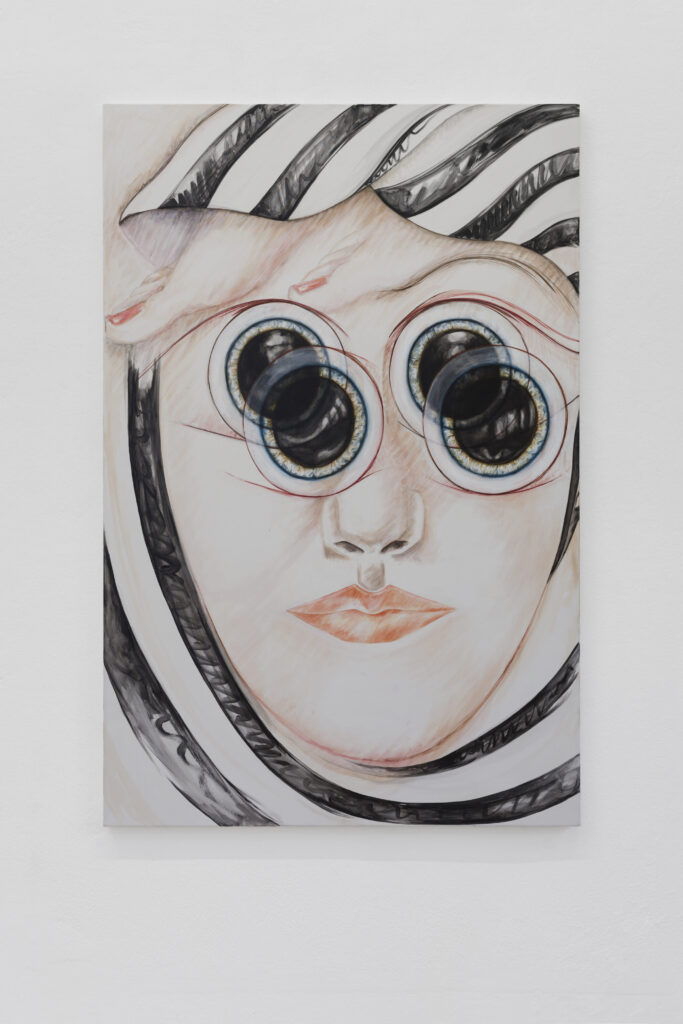

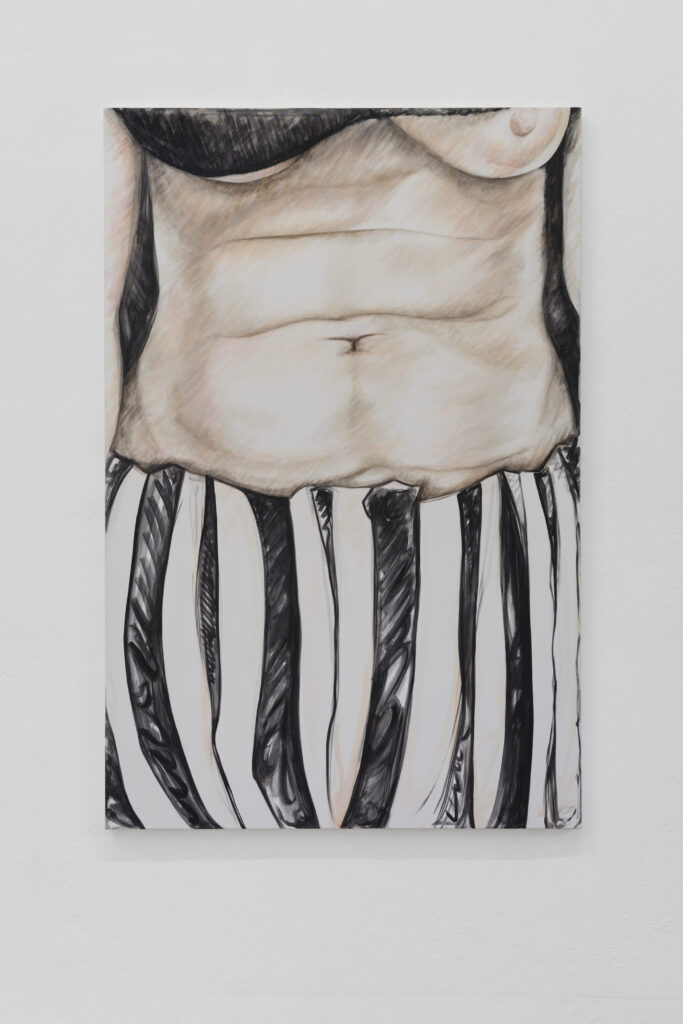

On the wall nearest to where we were sat in Catherine’s studio, three portraits were lined up in a row: a close up of a woman’s midri , a face with four enormous, tripped- out eyes, and a grimacing woman with her feet shoved up against the window of a car. Her soles were wrinkled like old fruit, or a body that has been submerged in water for a long time. Like all the gures, her skin was pickled milk green.

Throughout the day I had been drinking strong co ee. The combination of Catherine’s forensic pa- lette and my ca eine-induced jitters put me momentarily on edge, dredging up memories of previous perturbations. I told her that the three paintings reminded me of coming down from ecstasy. I was thinking of that feeling when joy begins to peel away in layers, and the world is a Russian doll that becomes increasingly unfamiliar the closer you get to the empty middle; when the face of your new best friend turns jagged and strange, the decor of the room you are in, bleak and tawdry; when you look down at yourself, or catch your re ection in the mirror, and your skin has turned cold and feral; when your body is a territory in which you are a stranger.

12.01.2019

As the colour of new life and potential, green is an ambassador for existential FOMO; for the fear that our salad days will wilt and then rot before we have made the most of them. In Sylvia Plath’s novel The Bell Jar, Esther Greenwood (a tting name) describes this particular strain of anxiety, using an image of a giant g tree laden with fruit. If picked, each g is guaranteed to deliver her a di erent, brilliant future, whether love, a career, exciting friends, or travel. “I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this g tree,” she says, “starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind which of the gs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the gs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.”

18.11.2018

On the farthest wall of Catherine’s studio was a large landscape painting. In the foreground, an abundant eld of green corn strained skywards, each ear reaching upwards in an ecstatic display of life. The painting reminded me of Vincent Van Gogh, the way that his landscapes are so overcome by vitality that they seem infected with it. Over this strange crop, and lling the sky, Catherine had painted what looked like a black metal gate, with ironmongery designed in an imitation of sunbeams. I have since wondered if it is more accurate to describe the scene as a barrier masquerading as nourishment, or a ourishing in containment. Or whether, in the end, there is any di erence between the two.

06.01.2019

In December, I wrote Catherine an email attempting to explain an atmospheric a inity between her paintings, and the hundreds Pierre Bonnard made of his wife, Marthe de Meligny, in the home they shared in the south of France. Marthe su ered from a form of anxiety triggered by being observed.

Perhaps because of this, Pierre made all his paintings of her from memory. Perhaps because of this, they are as a ectionate as they are fraught. A hazardous green leaks through the furniture and Marthe’s body. Often, Pierre covered her face in shadow, or he blended her features with the colours and patterns of the interior, as if he could no longer see where she ended and their home began. As if he could see her everywhere and nowhere: a side-e ect of intimacy and love that is familiar to many couples, families, and friends, for whom the boundaries between “you” and “me” have been corrupted. In my email, I tried to describe to Catherine the state of tender claustrophobia in which Bonnard’s paintings are suspended. “Perhaps it’s like trying to read a book”, she replied, “when it’s resting on your nose”.

22.01.2019

Claustrophobia is a feeling native to heat: those times of the year when the air thickens like cream and threatens to turn in the sun, and the sweat from the backs of your thighs becomes salty glue, sticking you to the furniture. Catherine and I both read Carson McCullers’ Southern novel, The Mem- ber of the Wedding, a story about a girl named Frankie Adams, and the listless summer she spends in a small and oppressively hot town. Frankie is in the queer no-mans-land of adolescence, too adult for childish games and too childish to belong among the adults. Her frustrations combine with the cli- mate, o setting a febrile state of mind. We agree that one of the things we like about the book is that nothing much happens, other than the accumulation of intensity, which gathers around Frankie like a thunderstorm that never breaks—a quality observable in each of the paintings I saw in Catherine’s studio. At least three times in our email correspondence, she sends me the same line:

“At last the summer was like a green sick dream, or a silent crazy jungle under glass.”

Photo: Marco Davolio

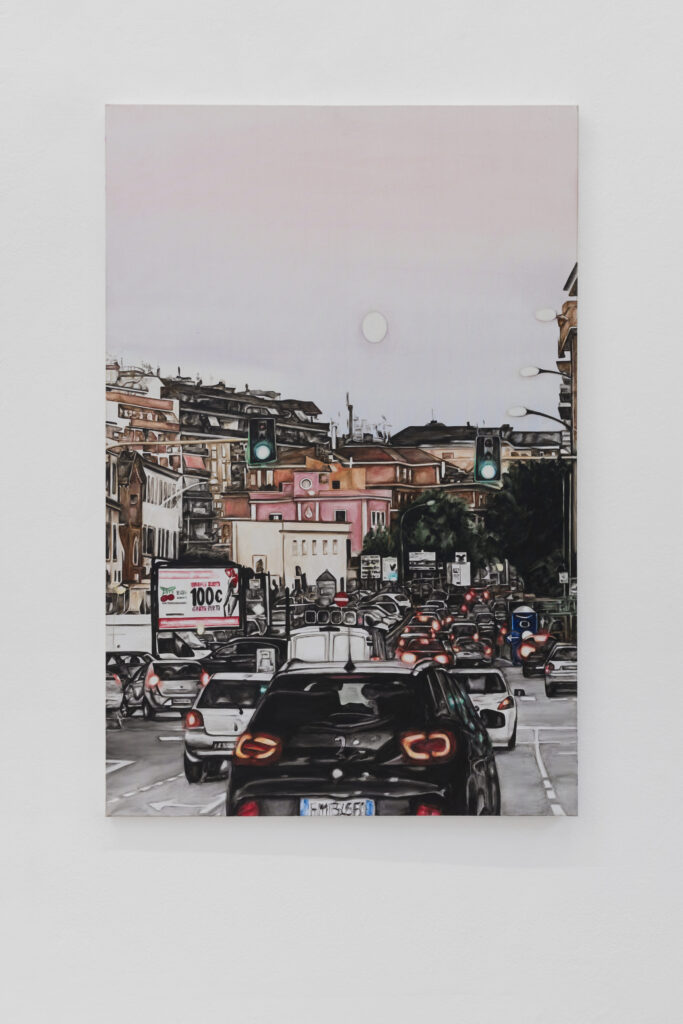

Catherine ParsonagePorta Furba, 2018

Catherine ParsonagePorta Furba, 2018

Acrylic on canvas

80x120cm Catherine ParsonageUntitled, 2018

Catherine ParsonageUntitled, 2018

Acrylic on canvas

80x120cm Catherine ParsonageEars of Corn,Throats of Wheat, 2018

Catherine ParsonageEars of Corn,Throats of Wheat, 2018

Acrylic on canvas

180x120cm Catherine Parsonagemoon lips, 2018

Catherine Parsonagemoon lips, 2018

Acrylic on canvas

25x35,5cm Catherine ParsonageRams/Room, 2018

Catherine ParsonageRams/Room, 2018

Acrylic and puff paste on canvas

180x120cm Catherine ParsonageStranger, 2018

Catherine ParsonageStranger, 2018

Acrylic on canvas

80x120cm Catherine ParsonageHalos (foxglove), 2018

Catherine ParsonageHalos (foxglove), 2018

Acrylic on canvas

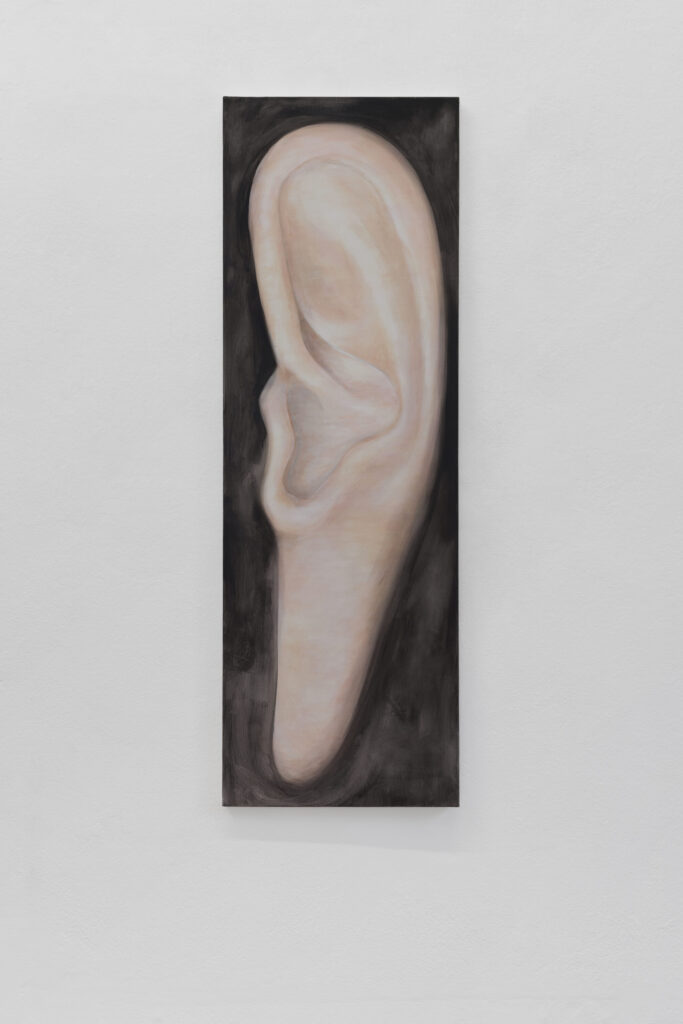

200x110cm Catherine ParsonageTo Pour Poison, 2018

Catherine ParsonageTo Pour Poison, 2018

Acrylic on canvas

40x120cm Catherine ParsonageUntitled, 2018

Catherine ParsonageUntitled, 2018

Acrylic on canvas

80x120cm

Catherine Parsonage (Wirral, 1989) lives and works between Rome and London. Recent solo exhibitions include: Present Future Section, Artissima, House of Egorn, Turin (2017), GRANPALAZZO, Bosse and Baum, Zagarolo (2016); Art Rotterdam, House of Egorn, Rotterdam (2016); a wrist that turns, House of Egorn, Berlin (2016). Recent group exhibitions include: Full For It: Tomaso De Luca and Catherine Parsonage, Garbo’s, Rome (2017), June Mostra, British School at Rome, Rome (2017), Le Nouveau Voyeurisme, Hotel Contemporary, Milan (2017); March Mostra, British School at Rome, Rome (2017); December Mostra, British School at Rome, Rome (2016). Parsonage has upcoming group exhibitions at Yellowspace, Varese & House of Egorn, Berlin (2018).